Monday, May 22, 2006

A “Nossa” Beit Knesset do Olival.

Alguém morreu em vão?

André Veríssimo*

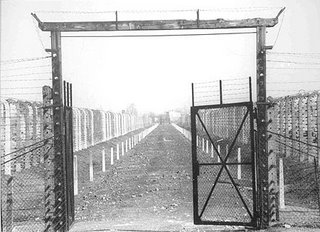

Outro dia dei comigo a passear pela Judiaria do Porto: a Medieval e a observar a Eichal da Sinagoga do Olival… Com umas quinze pessoas fui dialogando entre juristas, farmacêuticos, professores, militares, gestores, administradores e crianças, que quiseram saber o que somos, nós, os judeus…marranos. Eu falei e pensei e meditei no peso das palavras, das mitzvot, das pedras e na presença duma sinagoga vazia entregue inesperadamente ao cuidado dum Cura simpático, da Igreja vizinha, o que me flagelou moralmente desde o primeiro momento de tempo a memória por resgatar, … e a que falta da vida da Sepher Torá! E a pensar no Holocausto, na Shoah ibérica, do largo de s. Domingos de há 500 anos e na bestialidade recidiva de há 70 anos….É Hans Jonas que vem falar da não omnipotência de D.us. Baseando-se em argumentos ontológicos e teológicos e autenticamente religiosos resolve discutir nesta base uma omnipotência divina absoluta e ilimitada. A omnipotência divina só pode coexistir com a bondade divina ao preço da insondabilidade de D.us quer dizer, do seu carácter enigmático. Daí Jonas releva os três atributos em que a questão do homem sobre D.us recupera um sentido de incerteza próximo dos tempos de sofrimento: “ só um D.us de todo incompreensível se pode dizer que ao mesmo tempo é absolutamente bom e omnipotente e que tolera, ao mesmo tempo, o mundo tal como é. Dito de maneira mais geral, os três atributos em questão — bondade absoluta, omnipotência e compreensibilidade — estão numa relação tal que qualquer de dois deles exclui exclui o terceiro” Jonas, Hans, Pensar sobre Dios y otros ensayos, Herder, Barcelona, 1998, p. 207. Portanto, a pergunta é obsidiante em torno a qual dos três atributos descontinuar. “ A bondade, quer dizer, o querer o bem, é certamente inseparável do nosso conceito de D.us e não pode ser restringido. A compreensibilidade e cognoscibilidade estão duplamente condicionadas: pela essência de D.us e pelas limitações do ser humano, e em última instância está sujeita à limitação, porém sob nenhuma condição pode ser totalmente negada. O D.us absconditus, o D.us oculto, é uma ideia profundamente alheia à fé judia. É com base num racionalismo e num optimismo obtemperado que o judaísmo se baseia nos pressupostos racionais para o conhecimento de D.us. Uma teodiceia muito particular, uma vez que exclui a totalidade do conhecimento de D.us. “ A nossa doutrina, a Torah, baseia-se e insiste em que podemos entender a D.us, naturalmente, não de todo, porém algo dele, da sua vontade, das suas intenções e inclusive da sua essência, porque se nos deu a conhecer.” [Ib., pp. 207-208. A concepção da revelação, mandamentos, leis, das mediações como a língua e o entendimento, tornam os signos da comunicação da Alteridade de D.us não obscuros e inaceitável a concepção dum D.us oculto].Daí que se torne um escândalo para a inteligência a sustentação depois de Auschwitz da coerência entre os três atributos referidos: uma divindade omnipotente ou bem não seria infinitamente boa ou totalmente incompreensível (no seu domínio sobre o mundo, que é unicamente onde podemos compreendê-la). Se ele se torna compreensível até certo grau a sua Bondade deve ser compatível com a existência do mal, e só o pode ser se não é Omni-potente.Qualquer herança da tradição judia requer a consideração do poder de D.us como limitado por algo cuja existência por próprio direito e cujo poder de actuar por própria autoridade são reconhecidos por D.us mesmo. Poder-se-ia interpretar isto como uma concessão de D.us, que Ele pode revogar quando queira. O problema parece ser o da discrição da actuação de D.us e da sua ruptura com essa constituição ou regra de impassibilidade sempre que tormentos real e absolutamente monstruosos de seres humanos que infligem e infligiram a alguns outros, inocentes, de maneira unilateral. Porém não houve milagres de salvação. Durante os anos de atrocidades de Auschwitz, D.us permaneceu em silêncio. Em silêncio! Os milagres eram humanos, de povos que não recusaram o sacrifício da própria vida para salvar e atenuar, e que compartilhavam em tudo quanto era inevitável, o Destino de Israel. Esta tarefa incumprida de D.us é apontada por Jonas como um D.us que renunciou ao seu poder de Poder, ao seu poder de imiscuir-se nas coisas do mundo; o sentido do êxodo perdeu-se, porque a intervenção da “mão forte e do braço estendido” fez-se como intensidade da sua muda solicitação de objectivos por consumar.Os enunciados acerca do poder supremo de D.us da doutrina judaica, são para Jonas caducas: o prémio dos bons, o castigo dos maus e as profecias messiânicas. Daqui o significado espantosamente crítico dum significado do Shoah, que revela uma viragem nas preces (treze doutrinas) de Maimónides e na continuação duma fé controvertida pelo peso fatídico duma História actual que transmuta em sofrimento a promessa mil vezes repetida. A questão primacial do judaísmo pós-Inquisição e pós-Auschwitz é o do mal por vontade e não da causalidade. O acto de auto-alienação divina pressupõe a autonomia da liberdade no criado. A auto-limitação subsiste no Acto Criador com a sua unidade, deixando espaço à existência humana derivada duma acção de absoluta soberania de-si, de D.us. O conceito cabalístico de contracção TZIMTZUM, que significa também retirada, auto-limitação, responde a esta interpretação sacrificial de D.us, ou da hermenêutica do des-astre. Os actos de recolhimento, limitação, vazio, respeitam aos elementos, coisas que existem ao lado de D.us, sendo esta a medida de perseveração do ser das coisas no todo dentro do todo divino.Assim percebemos que não obstante esta limitação teologal da doutrina de Jonas, o sentido da plenitude do poder de D.us em Job é invertido em renúncia ao poder. Ainda que a conta fique por saldar de uma geração, e por fim que a superioridade do bem sobre o mal é o signo duma alteridade projectada para a possível paz do reino invisível. A compreensão desta paz passa pelo sofrimento daqueles que como Job sofrem para que a obra de D.us se cumpra, como sempre no tempo justo. Em Franz Rosenzweig, (La Estrella de la redención, Sígueme, Salamanca, p. 327), o tempo justo exprime-se num ser que não necessita de tempo, senão como redentor de Mundo e Homem, e isto, não porque Ele o necessite mas porque Homem o Mundo o necessitam. Pois para D.us o futuro não é uma antecipação. É o eterno, o único eterno, o Eterno. O vestígio do outro é em primeiro lugar o vestígio de D.us que nunca está aí. Pertence já ao passado. Essa a razão porque Levinas usa a terceira pessoa. ELE. Isso exprime uma impossibilidade. A de que ele a abandonou a si mesmo dizendo: não há graça neste sentido preciso. Ele está sempre ausente. E isso, Levinas “observa-o como vestígio do Outro no homem. Neste sentido todo o homem é vestígio do Outro. O Outro é D.us fazendo irrupção na palavra. Se tudo fosse dedutível o outro seria incluído no Eu. Tudo o que não é dedutível... expressa ainda a começo por um conceito dum D.us que é um “ELE”.Acrescenta num jeito de incessante adiamento do caos — o Shemah Israel.O Homem é acima de tudo consciência e responsabilidade. Esta responsabilidade é sempre a cada momento, a responsabilidade a respeito de certos valores. Não se trata de valores eternos. São assim valores passageiros que acontecem uma vez. Aquilo a que Max Scheler chama valores de situação. Os valores não se referem a uma situação mas estão perfeitamente adequados à pessoa. E são cambiáveis de pessoa para pessoa. Manifestam uma exigência de realização, que irradiam do mundo dos valores para a vida dos homens, tornando-se assim o imperativo concreto da hora no chamamento pessoal de cada indivíduo. E enquanto o homem não se dê conta do carácter específico da sua própria existência, que vive uma vez e de modo único, não estará em condições de viver a realização do que constitui a missão própria da sua vida como algo que verdadeiramente o obriga e do qual não pode desembaraçar-se. É nesta sentido que o sentido da vida se dá em termos de concepção geral dentro de três possíveis categorias axiológicas. Falamos de valores de criação, de vivência e de atitude. A primeira categoria realiza-se por intermédio dos actos, a segunda mediante o acolhimento passivo do universo pelo eu. Os valores de atitude realizam-se sempre que admitimos como tal algo que reputamos de irremissível, fatal como o destino. E é fatal que o estado de coisas se perpetue? Com respeito ao modo como cada um de nós o aceita se abre perante nós uma multitude de possibilidades de valor. Não cabe qualquer dúvida de que sabemos valorizar de um modo incomparavelmente elevado o sentido da vida e da memória e o valor moral do homem da comunidade, que não luta em vão. Atitude que nos cabe tomar para sabermos negociar o que nos fugiu da mão, num passado incerto…

* Pr. Associação Judaica KoaH.

André Veríssimo*

Outro dia dei comigo a passear pela Judiaria do Porto: a Medieval e a observar a Eichal da Sinagoga do Olival… Com umas quinze pessoas fui dialogando entre juristas, farmacêuticos, professores, militares, gestores, administradores e crianças, que quiseram saber o que somos, nós, os judeus…marranos. Eu falei e pensei e meditei no peso das palavras, das mitzvot, das pedras e na presença duma sinagoga vazia entregue inesperadamente ao cuidado dum Cura simpático, da Igreja vizinha, o que me flagelou moralmente desde o primeiro momento de tempo a memória por resgatar, … e a que falta da vida da Sepher Torá! E a pensar no Holocausto, na Shoah ibérica, do largo de s. Domingos de há 500 anos e na bestialidade recidiva de há 70 anos….É Hans Jonas que vem falar da não omnipotência de D.us. Baseando-se em argumentos ontológicos e teológicos e autenticamente religiosos resolve discutir nesta base uma omnipotência divina absoluta e ilimitada. A omnipotência divina só pode coexistir com a bondade divina ao preço da insondabilidade de D.us quer dizer, do seu carácter enigmático. Daí Jonas releva os três atributos em que a questão do homem sobre D.us recupera um sentido de incerteza próximo dos tempos de sofrimento: “ só um D.us de todo incompreensível se pode dizer que ao mesmo tempo é absolutamente bom e omnipotente e que tolera, ao mesmo tempo, o mundo tal como é. Dito de maneira mais geral, os três atributos em questão — bondade absoluta, omnipotência e compreensibilidade — estão numa relação tal que qualquer de dois deles exclui exclui o terceiro” Jonas, Hans, Pensar sobre Dios y otros ensayos, Herder, Barcelona, 1998, p. 207. Portanto, a pergunta é obsidiante em torno a qual dos três atributos descontinuar. “ A bondade, quer dizer, o querer o bem, é certamente inseparável do nosso conceito de D.us e não pode ser restringido. A compreensibilidade e cognoscibilidade estão duplamente condicionadas: pela essência de D.us e pelas limitações do ser humano, e em última instância está sujeita à limitação, porém sob nenhuma condição pode ser totalmente negada. O D.us absconditus, o D.us oculto, é uma ideia profundamente alheia à fé judia. É com base num racionalismo e num optimismo obtemperado que o judaísmo se baseia nos pressupostos racionais para o conhecimento de D.us. Uma teodiceia muito particular, uma vez que exclui a totalidade do conhecimento de D.us. “ A nossa doutrina, a Torah, baseia-se e insiste em que podemos entender a D.us, naturalmente, não de todo, porém algo dele, da sua vontade, das suas intenções e inclusive da sua essência, porque se nos deu a conhecer.” [Ib., pp. 207-208. A concepção da revelação, mandamentos, leis, das mediações como a língua e o entendimento, tornam os signos da comunicação da Alteridade de D.us não obscuros e inaceitável a concepção dum D.us oculto].Daí que se torne um escândalo para a inteligência a sustentação depois de Auschwitz da coerência entre os três atributos referidos: uma divindade omnipotente ou bem não seria infinitamente boa ou totalmente incompreensível (no seu domínio sobre o mundo, que é unicamente onde podemos compreendê-la). Se ele se torna compreensível até certo grau a sua Bondade deve ser compatível com a existência do mal, e só o pode ser se não é Omni-potente.Qualquer herança da tradição judia requer a consideração do poder de D.us como limitado por algo cuja existência por próprio direito e cujo poder de actuar por própria autoridade são reconhecidos por D.us mesmo. Poder-se-ia interpretar isto como uma concessão de D.us, que Ele pode revogar quando queira. O problema parece ser o da discrição da actuação de D.us e da sua ruptura com essa constituição ou regra de impassibilidade sempre que tormentos real e absolutamente monstruosos de seres humanos que infligem e infligiram a alguns outros, inocentes, de maneira unilateral. Porém não houve milagres de salvação. Durante os anos de atrocidades de Auschwitz, D.us permaneceu em silêncio. Em silêncio! Os milagres eram humanos, de povos que não recusaram o sacrifício da própria vida para salvar e atenuar, e que compartilhavam em tudo quanto era inevitável, o Destino de Israel. Esta tarefa incumprida de D.us é apontada por Jonas como um D.us que renunciou ao seu poder de Poder, ao seu poder de imiscuir-se nas coisas do mundo; o sentido do êxodo perdeu-se, porque a intervenção da “mão forte e do braço estendido” fez-se como intensidade da sua muda solicitação de objectivos por consumar.Os enunciados acerca do poder supremo de D.us da doutrina judaica, são para Jonas caducas: o prémio dos bons, o castigo dos maus e as profecias messiânicas. Daqui o significado espantosamente crítico dum significado do Shoah, que revela uma viragem nas preces (treze doutrinas) de Maimónides e na continuação duma fé controvertida pelo peso fatídico duma História actual que transmuta em sofrimento a promessa mil vezes repetida. A questão primacial do judaísmo pós-Inquisição e pós-Auschwitz é o do mal por vontade e não da causalidade. O acto de auto-alienação divina pressupõe a autonomia da liberdade no criado. A auto-limitação subsiste no Acto Criador com a sua unidade, deixando espaço à existência humana derivada duma acção de absoluta soberania de-si, de D.us. O conceito cabalístico de contracção TZIMTZUM, que significa também retirada, auto-limitação, responde a esta interpretação sacrificial de D.us, ou da hermenêutica do des-astre. Os actos de recolhimento, limitação, vazio, respeitam aos elementos, coisas que existem ao lado de D.us, sendo esta a medida de perseveração do ser das coisas no todo dentro do todo divino.Assim percebemos que não obstante esta limitação teologal da doutrina de Jonas, o sentido da plenitude do poder de D.us em Job é invertido em renúncia ao poder. Ainda que a conta fique por saldar de uma geração, e por fim que a superioridade do bem sobre o mal é o signo duma alteridade projectada para a possível paz do reino invisível. A compreensão desta paz passa pelo sofrimento daqueles que como Job sofrem para que a obra de D.us se cumpra, como sempre no tempo justo. Em Franz Rosenzweig, (La Estrella de la redención, Sígueme, Salamanca, p. 327), o tempo justo exprime-se num ser que não necessita de tempo, senão como redentor de Mundo e Homem, e isto, não porque Ele o necessite mas porque Homem o Mundo o necessitam. Pois para D.us o futuro não é uma antecipação. É o eterno, o único eterno, o Eterno. O vestígio do outro é em primeiro lugar o vestígio de D.us que nunca está aí. Pertence já ao passado. Essa a razão porque Levinas usa a terceira pessoa. ELE. Isso exprime uma impossibilidade. A de que ele a abandonou a si mesmo dizendo: não há graça neste sentido preciso. Ele está sempre ausente. E isso, Levinas “observa-o como vestígio do Outro no homem. Neste sentido todo o homem é vestígio do Outro. O Outro é D.us fazendo irrupção na palavra. Se tudo fosse dedutível o outro seria incluído no Eu. Tudo o que não é dedutível... expressa ainda a começo por um conceito dum D.us que é um “ELE”.Acrescenta num jeito de incessante adiamento do caos — o Shemah Israel.O Homem é acima de tudo consciência e responsabilidade. Esta responsabilidade é sempre a cada momento, a responsabilidade a respeito de certos valores. Não se trata de valores eternos. São assim valores passageiros que acontecem uma vez. Aquilo a que Max Scheler chama valores de situação. Os valores não se referem a uma situação mas estão perfeitamente adequados à pessoa. E são cambiáveis de pessoa para pessoa. Manifestam uma exigência de realização, que irradiam do mundo dos valores para a vida dos homens, tornando-se assim o imperativo concreto da hora no chamamento pessoal de cada indivíduo. E enquanto o homem não se dê conta do carácter específico da sua própria existência, que vive uma vez e de modo único, não estará em condições de viver a realização do que constitui a missão própria da sua vida como algo que verdadeiramente o obriga e do qual não pode desembaraçar-se. É nesta sentido que o sentido da vida se dá em termos de concepção geral dentro de três possíveis categorias axiológicas. Falamos de valores de criação, de vivência e de atitude. A primeira categoria realiza-se por intermédio dos actos, a segunda mediante o acolhimento passivo do universo pelo eu. Os valores de atitude realizam-se sempre que admitimos como tal algo que reputamos de irremissível, fatal como o destino. E é fatal que o estado de coisas se perpetue? Com respeito ao modo como cada um de nós o aceita se abre perante nós uma multitude de possibilidades de valor. Não cabe qualquer dúvida de que sabemos valorizar de um modo incomparavelmente elevado o sentido da vida e da memória e o valor moral do homem da comunidade, que não luta em vão. Atitude que nos cabe tomar para sabermos negociar o que nos fugiu da mão, num passado incerto…

* Pr. Associação Judaica KoaH.

Monday, May 08, 2006

La Descripción de Israel y los judíos en los libros de texto de la Autoridad Palestina

Estudiantes de 7 años

* Agrega la palabra correcta:Ellos, él, ella ____________ es el comandante de las fuerzas islámicas para la conquista de Jerusalem.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Segundo grado, 2a. parte, p. 42.

* Estudio de "Un poema sobre Palestina" de Mahmoud Al-Shalabi:Para mí, la promesa del Martirio es mi canción.Desde Jerusalem, construiré mi escalera hacia la eternidad.Nuestro idioma árabe, Segundo grado, 2a. parte, p. 51.

+ El maestro debe desarrollar brevemente un pensamiento sobre Palestina, por ejemplo:Los corazones árabes son devotos a Palestina; esperan el día en el que podrán liberarla, echar fuera al ladrón agresor y regresar a Jerusalem.Guía del maestro, Nuestro idioma árabe, Segundo grado, p. 188.

Estudiantes de 8 años

* Estudio del poema "Somos la juventud" Somos la juventud y el mañana es nuestro...Marcharemos a pesar de la muerteAdelante, adelantePodremos construir, dependemos de otrosPodremos perecer, pero no seremos humillados...Educación Nacional Palestina, Tercer grado, p. 70.

* Elabora un enunciado que contenga las siguientes palabras:... muere como un Mártir, defender, nuestro héroe, nuestra patria...Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Tercer grado, 1a. parte, pp. 8-9.

+ Objetivos específicos:3.b. La liberación de Jerusalem y su protección son deberes sagrados.4. (El alumno) debe desarrollar su amor por Jerusalem y su deseo de sacrificio para su liberación.(El maestro) debe hacer las siguientes preguntas:b. ¿Quién ocupa actualmente Jerusalem?c. ¿Cuál es nuestro deber para con Jerusalem?Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Tercer grado, pp. 130-131.

+ Desarrollar (en el alumno) el deseo de proteger a la patria (Palestina) de la avaricia de los invasores:Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Tercer grado, p. 133.

+ Para definir la palabra "ladrón", decir:Un ladrón es quien toma cosas de los otros por la fuerza. Aquí, el ladrón es el enemigo que tomó nuestra patria.- ¿Qué haremos si el enemigo intenta conquistar una parte (de la patria)?- ¿Cómo enfrentaremos y derrotaremos al enemigo?Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Tercer grado, p. 174

Estudiantes de 9 años

* El hijo: ¿Qué hizo el Mensajero de Dios para garantizar la seguridad de la población? El padre: El profeta hizo todo lo necesario para garantizar la seguridad y la paz de la población de Medina. Es por eso que llegó a un acuerdo con los judíos… Pero los judíos, que como siempre no quieren que la gente viva en paz… conspiraron en contra de los musulmanes. Sin embargo, los musulmanes estuvieron atentos y falló la atroz intriga de los judíos. Los musulmanes, liderados por el Profeta, los castigaron mediante muerte y destrucción.Lo que aprendo de esta lección:- A sacrificar la vida propia y las posesiones terrenales por Alá y la patria.- A soportar todas las dificultades y a creer en los decretos de Alá y en el destino que El ha determinado.- Los judíos son traidores e infieles.Educación Religiosa Islámica, Cuarto grado, pp. 44-45 y 55.

* La traición y la infidelidad son rasgos del carácter de los judíos y, debemos ser precavidos ante ellos.Educación Religiosa Islámica, Cuarto grado, p. 87.

* Lo que aprendo de esta lección:Pienso que los judíos son los enemigos del Profeta y de los creyentes.Educación Religiosa Islámica, Cuarto grado, 2a. parte, p. 67

* Estudio del poema "Larga vida para la Patria", de Mouhammad Mahmoud Sadiq:Oh mi país, mi tierra.Daría mi sangre por ti.Te he ofrecido el sacrificio de mi vida, acéptalo.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Cuarto grado, 2a. parte, p. 91.

Estudiantes de 10 años

* Hijo mío, recuerda que Palestina es tu país… y que su tierra está empapada con la sangre de los Mártires.El mapa que se muestra en esta sección incluye, bajo el nombre de Palestina, todo el territorio de Israel.Preguntas para la comprensión del texto:4. Nombra cuatro batallas gloriosas que se desarrollaron en la tierra de Palestina.7. ¿Por qué debemos pelear con los judíos y echarlos fuera de nuestro país?Recuerda que:- El resultado final e inexorable será la victoria de los musulmanes sobre los judíosNuestro Idioma Arabe, nivel 5, pp. 61-67.

* Ejercicio gramatical:Cambia el singular a plural. Ejemplo: Mártir, Mártires.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Quinto grado, p. 70.

* Ejercicio gramatical:Analiza: Hemos sacrificado Mártir tras Mártir.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Quinto grado, p. 74.

* En el siguiente enunciado, encuentra el sujeto y el complemento:La Yihad es un deber religioso para todos los musulmanes.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Quinto grado, p. 167.

* Ejercicio gramatical:Modifica los siguientes enunciados del modo pasivo al modo activo:- El enemigo fue matado.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Quinto grado, p. 167.

* Escribe cinco enunciados sobre las virtudes de los Mártires y su honroso status. Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Quinto grado, p. 201.

Estudiantes de 11 años

* Escribe seis renglones en los que les explicas a tus compañeros el valor supremo de la Yihad por Alá.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, 1a. parte, p. 29.

* Ejercicio gramatical:La forma plural:c. Un Mártir es honrado por Alá. Dos Mártires son honrados por Alá. Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, 1a. parte, p. 37.

* Ejercicio gramatical:Analiza:4.d El luchador de la Yihad murió como un Mártir mientras defendía la tierra de su Patria.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, 1a. parte, p. 71.

* Preguntas: ¿Por qué es deber de todo musulmán ser un luchador de la Yihad por Alá? Educación Islámica, Sexto grado, p. 146.

* Aprende de memoria el poema "Musulmanes" de Youssouf Al-KardaouiOh musulmanes, musulmanes, musulmanes, donde haya verdad y justicia, ahí se nos podrá encontrar.La muerte nos agrada y nos oponemos a ser humillados.Qué dulce es la muerte por Alá…Educación Islámica, Sexto grado, p. 151.

* Texto para ser aprendido de memoria:Bagdad. Te he traído amor desde Palestina.Te acordarás de mi carácter árabe, Bagdad, mi Yihad?…Y en tu tierra hay convoyes de martirio…No eres tú quien liberó Amuria…Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, 2a. parte, pp. 32-33.

+ (El alumno) sintetizará las ideas contenidas en el texto:El nexo entre Palestina y Bagdad es expresado por el arabismo, la Yihad por la liberación, y la esperanza de asistencia y victoria de su pueblo. El poeta… ve a Bagdad sólo a través de las sangrientas heridas de su tierra.La esperanza del poeta es que Bagdad encabece el convoy libertador hacia la Palestina herida…Pregunta 8:¿Cuál es tu verso favorito? ¿Por qué?Respuesta: El último verso, porque cada letra evoca un pueblo palestino que es la víctima de la ocupación (israelí).Los sitios evocados son Yafo (que es parte de Tel Aviv) y el acercamiento a Jerusalem Oriental.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, pp. 228-230

+ Ensayo: 1. Elabora enunciados que incluyan la siguiente expresión: el peligro sionista ha engendrado a la Yihad"2. Escribe seis renglones en los que les explicas a tus compañeros el valor supremo de la Yihad por Alá.Al término de esta lección, el alumno debe poder:- Hablar durante dos minutos acerca del "mérito de la Yihad por Alá".- Desarrollar el tema anterior en tres a cinco párrafos escritos.- Respetar a los luchadores de la Yihad y pedirle a Alá que se compadezca de aquellos que han muerto- Ser guiados por los luchadores de la Yihad que han peleado por Alá.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, p. 62.

+ Ejercicios lingüísticos:Los palestinos no pueden liberar Jerusalem mientras no estén unidos.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, p. 68.

+ A todo aquél que le pida sinceramente a Alá una muerte de Mártir, Alá lo llevará a la residencia de los Mártires, incluso si muere en su cama.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Sexto grado, p. 206.

+ Objetivos:4. (El alumno) debe estudiar las conspiraciones de los judíos en contra de los Profetas de Alá.5. El maestro debe fomentar el pensamiento individual mediante preguntas, tales como:b. Jesús invitó a los israelitas a que adoptaran la religión de Alá, y ellos respondieron, llamándolo mentiroso, atacándolo. ¿Qué indica su comportamiento (el de los israelitas)?Guía del maestro, Educación Islámica, Sexto grado, pp. 111-112.

Estudiantes de 12 años

* Un judío iba pasando… (y los judíos odiaban la unión lograda por los musulmanes, y se alegraban ante las disputas y argumentos que surgían entre ellos)… Por lo tanto, envió al hombre que estaba con él a que se sentara con ellos y les recordara de las guerras entre ellos…Discusión:4. ¿Por qué los judíos odian la unión musulmana y quieren causar divisiones en ella?5. Ejemplifica, basado en eventos actuales, los intentos atroces de los judíosEducación Islámica, Séptimo grado, pp. 16-19.

* Cuídate de los judíos, pues son traidores e infieles. Educación Islámica, Séptimo grado, p. 79.

* El Martirio es cuando un musulmán es matado por el nombre de Alá … Entonces, una persona que muere es denominada "Mártir"… El Martirio por Alá es la esperanza de todos los que creen en Alá y confían en Sus promesas.. El Mártir se regocija en el paraíso que Alá le ha preparado.Educación Islámica, Séptimo grado, p. 112.

* Los judíos adoptaron una actitud hostil y errada hacia la nueva religión. Rechazaron a Mahoma y lo llamaron mentiroso; pelearon en contra de su religión en todas las formas posibles y con todos los medios disponibles, y esta guerra continúa hasta el día de hoy; conspiraron en su contra junto con los hipócritas y los adoradores de ídolos, y continúan comportándose de esa manera.Educación Islámica, Séptimo grado, p. 125.

* Tema de ensayo: "¿Cómo liberaremos la tierra que nos fue robada?"Utiliza los siguientes conceptos: Unidad árabe, fe verdadera en Alá, armas ultra modernas y municiones, uso del petróleo y otros recursos naturales como armamento en la lucha de liberación.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Séptimo grado, p. 125

* Estudio del poema "Madre":Madre, me voy a ir pronto, prepara la mortajaMadre, me estoy dirigiendo hacia la muerte… No voy a titubearMadre, no llores por mí si caigoYa que la muerte no me asusta, y mi destino es el de morir en el martirio.Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Séptimo grado, p. 63

+ ¿Por qué le pide el poeta a su madre que no llore por él? Respuesta: Porque él desea convertirse en un Mártir por Alá, y no le tiene miedo a la muerte.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Séptimo grado, p. 303.

+ En todas las circunstancias, la motivación del creyente que lucha por la Yihad debe ser:"Alá es grande…"Objetivos específicos:(El alumno) debe memorizar los temas principales del texto:La determinación de morir por AláPara el creyente, el Martirio por Alá es la parte más alta de la nobleza.Guía del maestro, Nuestro Idioma Arabe, Séptimo grado, p. 301.

+ (El alumno) debe desear convertirse en uno de los Mártires de Alá. Guía del maestro, Educación Islámica, Séptimo grado, p. 143.

+ El maestro puede… hacer las siguientes preguntas:a. ¿Cómo podemos educar a nuestros hijos para que quieran convertirse en Mártires por Alá?Es preferible que (el maestro) se enfoque en los siguientes elementos:a. El deseo de convertirse en un Mártir por Aláb. El amor del papel de Mártir por Alá.Preguntas generales:5. ¿Por qué los musulmanes aspiran a morir por Alá?Actividades de énfasis:5. Escribe cómo pueden, según tú, los musulmanes ser dirigidos a la Yihad y a desear convertirse en Mártires por Alá. Guía del maestro, Educación Islámica, Séptimo grado, pp. 144-147.

Estudiantes de 13 años

* Como fue decidido por la Liga de las Naciones en 1929, el muro de Al-Buraq es el muro sudoccidental de la Mezquita de Al-Aqsa. Los judíos declaran que ese sitio es suyo, y lo llaman "Muro de los Lamentos"; pero eso no es cierto.Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Octavo grado, p. 103.

* Estudio del poema "Palestina" de Mouhammad Tah:¡Hermanos míos! Los opresores (Israel –ed.) han excedido los límites. Por lo tanto la Yihad y el sacrificio son un deber… Lancen su espadas y después de eso no regresará a su funda… Reunámonos para la guerra, con sangre roja y fuego encendido… La muerte nos llamará y la espada será afilada para dicha matanza… Oh Palestina, los jóvenes rescatarán tu tierra. Oh Palestina, te defenderemos con nuestros pechos descubiertos. Por lo tanto, ¡ya sea vida o muerte!Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Octavo grado, p. 103.

* Preguntas para la comprensión del texto:2. ¿Quiénes son los "opresores" a los que el poeta se refiere en el primer verso?3. ¿Cuál es el camino a la victoria sobre el enemigo que menciona el poeta?4. El poeta insta a los árabes a emprender la Yihad. Indica el verso en el que lo hace.Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Octavo grado, pp. 120-122.

* Estudio del poema "Bayonetas y Antorchas":En tu mano izquierda llevabas el Corán. Y en la derecha una espada árabe… Hoy es el día de tu matrimonio… Has vivido como hombre libre, moriste como hombre libre. No estás muerto, pues Alá, en justicia, te ha llevado al paraíso… Sin sangre no se liberará ni siquiera un centímetro. Por lo tanto, avanza gritando: "Alá es grande".Comprensión (del texto):2. El poema contiene los siguientes temas:- El Mártir ha defendido su patria con valor, y murió gloriosamente. - La memoria del Mártir se queda en este mundo y en el venidero.Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Octavo grado, pp. 131-134.

* Los habitantes de Medina se involucraron en la agricultura y el comercio y la mayoría de los mercaderes eran judíos. Esto llevó (a los judíos) a su ganancia del control de la mercancía. Cuando el Profeta y sus acompañantes llegaron a Al-Medina, el Profeta emprendió la acción para liberar la economía del control judío… y entonces el comercio en el mercado se basó en la justicia y la honestidad, lejos y retirado de la explotación, el control y la usura (judía)…4. El Mensajero tomó medidas para liberar la economía musulmana del control judío. Explica.Educación Islámica, Octavo grado, pp. 63-64.

* El musulmán se sacrifica por su fe y lucha una Yihad por Alá. No conoce la cobardía porque entiende que el momento de su muerte ya está ordenado y que su muerte como Mártir en el campo de batalla es preferible a morir en la cama.Educación Islámica, Octavo grado, p. 176.

Estudiantes de 14 años

* Padre mío, a aquél que luchó una Yihad en nombre de Alá y defendió su religión y es matado por El, ¿las palabras verdaderas de Alá le aplican?- Bien dicho, mi joven hijo.- Gracias, padre mío. Le pido a Alá que nos provea de una muerte de Mártir y que nos reúna (en la muerte) con los Profetas, los honestos y los Mártires.Los Usos del Idioma, Noveno grado, 2a. parte, p. 35.

* De la expedición de Uhud y del episodio con la tribu (judía) de Al-Nadir, se pueden aprender numerosas lecciones:6. La traición y la infidelidad son rasgos del carácter de los judíos y uno debe prevenirse de ellos.Educación Islámica, Noveno grado, pp. 86-87.

* Cuando el Profeta llegó a Al-Medina se encontró que, entre los habitantes, había tribus judías… En muchos casos, estos judíos, con sus conocidas habilidades y charlatanerías, fomentaban disputas internas.Educación Islámica, Noveno grado, pp. 78-79.

* Cuando los judíos vieron al ejército musulmán acercarse a ellos, huyeron hacia su fortaleza… El Mensajero de Alá rechazó (su petición) y les demandó someterse a él… Saad emitió la sentencia:… Los hombres (judíos) serían matados, su propiedad sería dividida, y las mujeres y los niños se volverían prisioneros. Lecciones que aprender:Uno debe prevenirse de la guerra civil que los judíos intentan incitar y de sus proyectos en contra de los musulmanes.Educación Islámica, Noveno grado, pp. 92-94.

* Escribe en tu libro de ejercicios: ¿Durante qué tiempo fue finalmente limpiada de judíos la Península y quién fue el que recomendó su remoción?Educación Islámica, Noveno grado, pp. 107-109.

* Escribe en tu libro de ejercicios: Un evento que demuestre el fanatismo de los judíos en contra de los musulmanes o los cristianos en Palestina Educación Islámica, Noveno grado, p. 182.

Estudiantes de 15 años

* Al Makhtar… fue uno de los más conocidos luchadores de la Yihad en Libia en contra de los imperialistas italianos…"¿Por qué peleaste una guerra tan cruel en contra del gobierno italiano?- "Porque mi religión así me lo manda…"El Espíritu del Texto:Los Mártires, luchadores de la Yihad, son las personas más veneradas después de los Profetas… Mueren por Alá, sacrificándose por sus principios y por proteger a su patria y el honor de su pueblo. Los vivos recuerdan a sus Mártires y los honran enseñándoles a sus hijos la historia de sus vidas, generación tras generación.Discusión y Análisis:7. ¿Qué te recuerda la lucha del pueblo libio en contra de los invasores?Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Décimo grado, pp. 99-105.

* El Martirio es vida.Textos Literarios y de Lectura, Décimo grado, p. 171.

+ El alumno adquirirá los siguientes valores: - Combatir al imperialismo en todas sus formas.- Ser guiado por las acciones de los luchadores árabes de la Yihad. Guía del maestro, Historia Moderna Arabe y Problemas Contemporáneos, Décimo grado, p. 11.

Estudiantes de 16 años

+ En la vida de la nación (el alumno) debe valorar la importancia de la Yihad y de la muerte en combate…Pide a un grupo de alumnos que prepare ensayos sobre los siguientes temas:e. Desea la muerte (en el Martirio) y recibirás vida. Manual del maestro, Cultura Islámica, Undécimo grado, pp. 149-150.

+ Conceptos:Movilización general armada, Obligación general, Obligación individual.Relaciona estos conceptos con la situación actual de los musulmanes.¿En qué obliga la ley de la Yihad a los musulmanes de hoy?Tipos de Yihad¿Por qué tiene la nación musulmana que ser una nación de Yihad?Manual del maestro, Cultura Islámica, Undécimo grado, pp. 155-156.

+ Lección 2: La importancia de la Yihad en la vida musulmana.Objetivos:2. El alumno debe desarrollar explícitamente la necesidad de la Yihad para proteger a los musulmanes y preservar su religión.3. Debe definir métodos para difundir el islam entre la población.4. Debe subrayar el papel de la Yihad en la obtención de gloria y victoria para la nación y para el honor del Mártir. 5. Debe subrayar la importancia del espíritu de la Yihad para fortalecer a la nación. Manual del maestro, Cultura Islámica, Undécimo grado, p. 157.

+ El alumno debe ser capaz de:6. Describir los esfuerzos de Saladin por liberar a Jerusalem de la conquista de los cruzados.7. Hacer un paralelismo entre la situación de Jerusalem durante la invasión de los cruzados y en la actualidad.Valores y dirección:4. Ser guiados por la Yihad musulmana con el objeto de liberar la tierra musulmana de los ladrones.Manual del maestro, Cultura Islámica, Undécimo grado, p. 168.

+ Lección 7: La YihadLa resistencia musulmana a la invasión sionista.Objetivos:3. Presentar la política musulmana, en cuanto a su rechazo de la conquista sionista de Palestina. 9. Estar convencidos de que la Yihad es el medio para liberar a Palestina de la conquista sionista.10. Honrar a los luchadores de la Yihad y a los Mártires, cuya sangre fue derramada en la tierra de Jerusalem. Valores y dirección:- Aborrecer a los imperialistas y sionistas maliciosos que causaron el robo de Palestina y la explotación de su pueblo. - Respetar el esfuerzo realizado por liberar a Palestina de la conquista sionista.- Adoptar las posiciones utilizadas por los pensadores religiosos y los líderes (militares) respecto a la Yihad como el medio para luchar en contra de la ocupación sionista.Manual del maestro, Educación Islámica, Undécimo grado, p. 168.

+ Valores y dirección:2. Desarrollar el amor del Mártir por Alá.Manual del maestro, Educación Islámica, Undécimo grado, p. 158.

+ Objetivos:8. (El alumno) tratará de desarrollar en sí mismo el espíritu de la Yihad y la indiferencia frente a la muerte.Manual del maestro, Educación Islámica, Undécimo grado, p. 161.

Estudiantes de 17 años

+ Objetivos:11. (El alumno) debe establecer la relación entre la avaricia de los judíos en los países musulmanes y su odio por la fe islámica.Métodos de enseñanza:1) Películas educativas que esclarecen ciertos problemas del mundo islámico y los peligros que lo amenazan como:a) La invasión sionista.b) Las prácticas terroristas del sionismo. Preguntas propuestas: 3. ¿Cuál es la posición de las naciones árabes respecto a la agresión judía en las tierras musulmanas de Palestina? Detalla tu respuesta y relaciónala, lo más posible, con la creencia islámica.Actividades de énfasis:1. Organizar una mesa redonda o conferencia…f. Palestina es un país musulmán y así debe permanecer.2. Los grupos de estudiantes deben preparar reportes sobre los siguientes temas:c. La liberación de Palestina es una responsabilidad común de todos los musulmanes. Valores y dirección:1) La creencia de que Palestina es un país y que el problema sólo se solucionará a través de su liberación.3) La acción para liberar Palestina y unir a todos los musulmanes para confrontar todas las formas de invasión extranjera.Guía del maestro, Cultura Islámica, Duodécimo grado, pp. 169-180.

+ (El alumno) debe retener las siguientes ideas generales:a. El sionismo es un movimiento racista y agresor.b. La superioridad racial es la esencia del sionismo y del fascismo-nazismo(El alumno) debe entender la influencia negativa del sionismo en el progreso y renacimiento árabe.Guía del maestro, Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, p. 12.

* Desde tiempos remotos, la comunidad cristiana de Europa odió a los judíos. Los judíos, quienes fueron dispersados por los romanos, permanecieron atrincherados en los valores de su primer libro (la Biblia). Pronto, esto fue de la mano con el aislamiento racista predicado en el Talmud, y con un comportamiento destinado a corromper y destruir la sociedad en la que vivían.Existen un número de razones por las cuales los europeos persiguieron a los judíos, en cualquier lugar en el que se encontraban:1. La Biblia está llena de textos que confirman la tendencia de los judíos hacia el extremismo racial y religioso y actúan en un espíritu de odio hacia las otras naciones… los judíos europeos fueron odiados debido a sus creencias, que eran hostiles hacia el cristianismo, y por su aislamiento – no se mezclaban con las comunidades occidentales y continuaban viéndolas con desconfianza. Otra razón del odio en su contra, radica en que tomaron el control de la economía…2. La razón principal por la que las naciones del mundo persiguieron a los judíos es por su sentimiento de superioridad racial, religiosa, cultural y política y, por el hecho de que sus contactos con las naciones estuvieron basados en ese sentimiento.3. Se especializaron en la usura y en actividades de cambio de dinero y eso también influyó en el odio hacia los judíos por parte de las naciones del mundo… Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, pp. 121-122.

+ Objetivos:5. (El alumno) llegará a la siguiente conclusión: porque el mundo odia a los judíos.6. (El alumno) explicará por qué los europeos persiguieron a los judíos.Guía del maestro, Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, p. 151.

+ 1. El maestro comenzará por incitar a los alumnos a expresar lo que saben respecto al sionismo.2. El maestro dividirá la clase en dos grupos. Distribuirá documentos, que incluyen los siguientes textos: "Extractos del Talmud…". "Un judío tiene derecho a…" y "Discriminación racial". Después, guiará a los alumnos para que lleguen a las siguientes conclusiones:a. El significado de discriminación racial.b. Los aspectos racistas del movimiento sionista.Guía del maestro, Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, pp. 152-153.

* Está escrito en el Talmud:"Somos (los judíos) el pueblo de Dios en la tierra… (Dios) ha forzado a los humanos, animales, naciones y a todas las razas, a servirnos, y nos dispersó por todo el mundo para que dominemos y reinemos sobre ellos. Debemos otorgar a nuestras preciadas hijas a los Reyes, Ministros y Príncipes, y presentar a nuestros hijos dentro de varias religiones; así ejerceremos el control absoluto sobre todos los países. Debemos engañarlos (a los no judíos) y fomentar disputas entre ellos, para que luchen uno en contra del otro… Los no judíos son cerdos que fueron creados como humanos para que sirvan a los judíos, y Dios creó el mundo para (los judíos)".Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, p. 120.

Comentario: la fabricación de citas falsas del Talmud es una técnica muy antigua. La propaganda nazi la utilizó sistemáticamente y grupos neonazis continúan diseminando textos similares en todo el mundo. Un análisis detallado de la "cita" anterior podría tal vez llevar a la identificación de la fuente y descubrir en dónde encontraron los autores de este libro la substancia de su discurso antisemita. De cualquier forma, esta terrible falsificación parece gozar de cierta notoriedad entre la comunidad palestina ya que "la Guía del Maestro" la convierte en una actividad de "enriquecimiento" muy elaborada, como se puede ver en el siguiente apartado.

+ (El maestro) distribuirá a sus alumnos una tabla que contiene numerosas citas del Talmud. Ellos las debatirán, confirmando su naturaleza de odio, y señalarán los hechos que las contradicen.A esto le sigue una tabla de dos columnas titulada "Las creencias talmúdicas de los judíos". La primera columna se refiere a "La expresión (del Talmud)"; la segunda está vacía y los alumnos deben escribir en ella "La evidencia que contradice (a tal expresión)". Las supuestas "expresiones talmúdicas" enlistadas en la primera columna son:- Somos el pueblo de Alá en esta tierra y las bestias humanas están destinadas a servirnos.- Alá creó el mundo para los judíos.- Un judío tiene el derecho de engañar a un no judío.- El espíritu del judío es noble, el del no judío es satánico.- El Señor les otorgó Palestina a los judíos como su Tierra PrometidaGuía del maestro, Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, p. 153.

+ (El maestro) distribuirá el texto titulado "El peligro judío en Palestina". Este texto será presentado como un problema… (Los estudiantes) deberán sugerir soluciones para superar el problema.Guía del maestro, Historia Contemporánea de los Arabes y del Mundo, Duodécimo grado, p. 155.

David Diaz

Asoc. Cultural Sefardí 'Atasé'

Wendy Shalit

Wendy Shalit was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and received her B.A. in philosophy from Williams College. Her essays have appeared in The Wall Street Journal, Commentary, City Journal, and other publications. Her book, A Return to Modesty, was published by The Free Press in 1999, and last year was reissued in paperback by Touchstone Books in an edition that includes questions for classroom use. (Simon & Schuster: New York, 1999; 291 pages; $13)

Review by Patrick Hurd

The lack of one generation’s ability to keep pace with the next generation became known as the "generation gap" in the 1960’s and lent itself to that ever popular teenage whine, "You just don’t understand!" The increasing pace of the 21st century in America has contributed to faster shifts in cultural trends making it more and more difficult for parents to keep pace with the trends influencing their children.

The lack of one generation’s ability to keep pace with the next generation became known as the "generation gap" in the 1960’s and lent itself to that ever popular teenage whine, "You just don’t understand!" The increasing pace of the 21st century in America has contributed to faster shifts in cultural trends making it more and more difficult for parents to keep pace with the trends influencing their children.More frequently than parents are willing to admit, the teenage complaint is accurate. The pace at which fads come and go in our society make it very difficult for parents to have a wise response or to even know if they should have a response. While television and radio may be of some help in keeping parents abreast of the latest craze enticing the heart and soul of their children, these mediums of popular culture serve more to exasperate the problem than to inform and do nothing to explain the pressures placed on our young people to conform to the latest trend.

A Return To Modesty is, in part, a young lady’s account of the pressure of conformity she experienced upon entering college and generally upon all young women and their sexual identity. While Miss Shalit was a student at Williams College, she wrote a column for Commentary called "A Ladies Room of One's Own," about the indignity of having to live in a dorm with coed bathrooms. When the piece was later published in Reader's Digest, Miss Shalit says she received hundreds of letters from young women sharing the same embarrassment, but who had been too intimidated to express it. Miss Shalit combined the flood of responses she received and her observations of ladies on campus with ample documentation from outside sources and studies to formulate her highly controversial book.

My recommendation of A Return To Modesty to you is based on three notable characteristics of her book:

1. Miss Shalit, who is from a Jewish background and was not a professing Christian at the time of authoring the book, nevertheless argues her position from a Christian worldview. The Christian community should be quick to acknowledge work done on the foundation of a Christian worldview, especially when done by a non-Christian. To do so glorifies God.

2. For children who have not been socialized in or received sex education from the public school system, A Return To Modesty can be used to fill a gap in their training and education or to re-educate those who have. It can be useful in preparing them (especially the girls) for the "default" and unspoken sexual presuppositions shared by the rest of society.

3. A Return to Modesty has helped me as a parent to become better aware not only on the debate of sexual roles on a national level, but also the recent trends within the teenage and single dating scene, such as "hooking up and "freaking" (picture).

The basic argument of A Return To Modesty is that the feminist movement, in an effort to raise the standard of womanhood, began a process of erasing differences between men and women that has progressed to the point that any and all distinguishing characteristics between the sexes (physically, emotionally, psychologically, and societally) are open for challenge. According to Miss Shalit, while there may have been benefits to women as a whole, the backlash of negative repercussions to women as individuals and to womanhood in general has far outweighed the gains made, namely increasing violence against women and increasing psychological disorders.

"I was born in 1975, and from anorexia to date-rape, from our utter inability to feel safe on the streets to stories about stalking and stalkers, from teenage girls finding themselves miserably pregnant to women in the late 30s and early 40s finding procreation miserably difficult, this culture has not been kind to women. And it has not been kind to women at the very moment that it has directed an immense amount of social and political energy to ‘curing’ their problems." (page 8)

Miss Shalit asserts that the feminists are to blame for using the same ideology to battle against the rise of abuses against women that actually caused the problem. Thus, they continue to throw fuel on the fire. But the feminists are not the only ones guilty of promoting crimes against women. Conservatives are to blame for ignoring the outcries of the feminists about the rising abuse of women, claiming that the feminists are exaggerating and politicizing the problem for their own gain and, therefore, conservatives do nothing but publicly minimize the situation. Her complaint, therefore, is that there really is a problem in our society but that the feminists’ solution is all wrong and the conservative’s ignorance is worse than wrong.

"First, I want to invite conservatives to take the claims of the feminists seriously. That is, all of their claims, from the date-rape figures to anorexia to the shyness of teenage girls, even the number of women who say they feel ‘objectified’ by the male gaze. I want them to stop saying that this or that study was flawed; or that young women are exaggerating; or that it has been proven that at this or that university such-and-such a charge was made up. Because ultimately, it seems to me, it doesn’t really matter if one study is flawed or if one charge is false. When it comes down to it, the same vague yet unmistakable problem is still with us." (page 9)

The main thrust of A Return To Modesty is that the most important distinguishing characteristic differentiating between women and men is modesty, that the feminist have effectively won the battle eradicating modesty as a womanly virtue in America, and that the successful eradication can be directly correlated with the rise of crimes and abuses against women today.

"I propose that the woes besetting the modern young woman – sexual harassment, stalking, rape, even ‘whirlpooling’ (when a group of guys surround a girl who is swimming and then sexually assault her) – are all expressions of a society which has lost its respect for female modesty." (page 10)

To support her thesis, Miss Shalit uses the Christian worldview to establish modesty as "a reflex, arising naturally to help a woman protect her hopes and guide their fulfillment – specifically, this hope for one man." (page 94) In other words, modesty is not a product of societal dogma but, rather, an inherent virtue of both men and women, as natural as breathing, but more forceful in women. Though Miss Shalit doesn’t say it explicitly, one comes to the conclusion that she promotes the belief that modesty is implanted within us by our Creator rather than developed through external pressures or behavioral modification.

Modesty, which may be provisionally defined as an almost instinctive fear prompting to concealment and usually centering around the sexual processes, while common to both sexes is more peculiarly feminine, so that it may almost be regarded as the chief secondary sexual character of women on the psychical side. -- HAVELOCK ELLIS, 1899

While a created order may be subtly implied throughout her book, she adamantly and unapologetically defends her position insisting on the differing nature and roles between men and women. Her first encounter of the notion that there are no differences between the genders was in class at Williams College. When she spoke out in favor of male/female differences she was declared an "essentialist" by her classmates (one who believes there is a difference between men and women) and quickly discounted as someone who had anything to offer to the discussion.

Indeed, much of A Return To Modesty is dedicated to identifying the male/female differences as they relate to the advancement of a woman’s safe and contributory place in society. "Modesty acknowledged this special vulnerability [of the differences between the sexes], and protected it. It made women equal to men as women. Encouraged to act immodestly, a woman exposes her vulnerability and she then becomes, in fact, the weaker sex. A woman can argue that she is exactly the same as a man, she may deny having any special vulnerability, and act accordingly, but I cannot help noticing that she usually ends up exhibiting her feminine nature anyway, only this time in victimhood, not in strength." (page 108)

"Not only do we think there are differences between the sexes, but we think these differences can have a beautiful meaning – a meaning that isn’t some irrelevant fact about us but one that can inform and guide our lives. That’s why we’re swooning over nineteenth-century dramas and clothing. We want our dignity back, our ‘feminine mystique’ back, and, along with it, the notion of male honor." (page 140)

"Today we want to pretend there are no differences between the sexes, and so when they first emerge we give our little boys Ritalin to reduce their drive, and our little girls Prozac to reduce their sensitivity. We try to cure them of what is distinctive instead of cherishing these differences and directing them towards each other in a meaningful way." (page 153)

Her Christian worldview includes observations of the repercussions of the feminist movement on men and manhood also. "Too many egalitarians equate male gentleness or protectiveness with subordination, while too many conservatives equate it with effeminacy. Both sides are wrong. A man should be gentle around a woman. That’s part of what it means to be a man. We need to flip everything around again and associate manhood with knowing how to behave, not misbehave, around women." (page 147) Thus she asserts that one aspect of manhood is acting honorably toward women and that by erasing the male-female distinctions we have raised a generation of boys that has been mis-trained and, thus, short-changed in their manhood.

Closely associated with female modesty and male honor is the idea of human dignity for both genders. Miss Shalit asserts that men are less boorish when expected to recognize and act modestly toward women thus exalting their stature as man rather than mere beast. Likewise, the woman is acknowledged as a real person deserving of human dignity and respect rather than as a piece of property to be exploited at the will of any man who comes along.

"You may think you see me, the modestly dressed woman announces, but you do not see the real me. The real me is only for my beloved to see. Therefore, whatever you may say or think about me doesn’t really matter. The woman who complains about sexual harassment or ‘elevator eyes’ is not a frail, weak woman, nor is she the invention of a few radical feminists. She is, rather, a woman exposed and expressing a very real fear: that the one who is judging her is not the one who loves her, not the one who knows the ‘real’ her. Hence, he is presuming. A respect for modesty would prevent men from leering, from presuming to judge women whom they have not earned the trust of." (page 137)

There are three additional ways in which Miss Shalit articulates the Christian worldview to support her case. First, she argues that the failure of the feminist movement is its inability to anticipate the fallout from its faulty ideology on different levels of society. She identifies some of these effects thus promoting the biblical view of integration in the created order rather than isolation. Her proposed solution supports the same integration ideology as well as promoting the biblical model of blessings for conformity to the created order and curses for rebelling against the created order.

Second, Miss Shalit’s proposed solution shows concern for the particulars (individual women) and the whole (womanhood) whereas she identifies that the feminist movement is concerned solely for the whole with little or no regard for the particulars and their suffering.

Third, Miss Shalit employs a linear view when explaining the course of history that has brought us to where we are today, rather than a circular or evolutionary view that focuses on the swing of the pendulum or reoccurring cycles. Accordingly, she does not propose that today’s sexual atmosphere is a passing fad, one that we only need to learn to deal with until it is gone. Rather, she proposes that the consequence of causes were put into place by prior generations and, thus, the solution is to begin implementing the right causes today for the sake of future generations.

A Return To Modesty is a call for the return to youthful innocence, naivete, romanticism, idealism, and hope. It is a call for human dignity according to the created order. It is a call for men to be manish rather than machine and women to encourage men to treat them with respect and dignity. It is a call for us all to realize our strengths through submitting to our weaknesses.

"First, by not having sex before marriage, you are insisting on your right to take these things seriously, when many around you do not seem to. By reserving a part of you for someone else, you are insisting on your right to keep something sacred; you are welcoming the prospect of someone else making an enduring private claim to you, and you to him. But more significantly, not having sex before marriage is a way of insisting that the most interesting part of your life will take place after marriage, and if it’s more interesting, maybe then it will last. And, if the hope of modesty continues, if it lasts, maybe then you can finally be safe. Instead of living in dread, feeling slightly hunted, afraid someone will call us to account and abandon us, maybe then we can rest. At a time when everyone else seems to be giving up hope, a return to modesty represents a new start. Modesty creates a realm that is secure from an increasingly competitive and violent public one." (page 212)

What do you think about this issue? Give us your FEEDBACK.

To review Miss Shalit's article, Modesty Revisited, click HERE to go to Hillsdale College.

O leitor observante

ESSAY; The Observant Reader

By WENDY SHALIT

Published: January 30, 2005

JONATHAN ROSEN'S novel ''Joy Comes in the Morning'' features a beatific Upper East Side Reform rabbi named Deborah whose days are spent reassuring insecure converts, studying the Talmud and cuddling deformed newborns whose parents have rejected them. This paragon is, we are told, like a ''plant . . . nourishing herself directly from the source.'' But if Deborah is a plant, she's certainly not a clinging vine. When she propositions a man named Lev, it's with a sexy whisper: ''I'm a rabbi, not a nun.''

In contrast, Deborah's Orthodox ex, Reuben, is a Venus' flytrap. Although he wasn't supposed to touch her, he had no qualms about sleeping with Deborah, a slip she's sure was ''only one of the 613 commandments he had violated, but perhaps the one he most easily discounted.'' Curiously, Reuben showed ''more anxiety about the state of her kitchen'' than he did about spending the night -- next morning, he went through the dishes to make sure she had separate sets for milk and meat.

You might think Reuben is just a guy with a problem, but the problem may also be the author's. In the course of the novel, Rosen dismisses modern Orthodox men as ''macho sissies'' and depicts ''pencil-necked'' Orthodox boys ''poring over giant books instead of looking out the window at the natural world.'' Rosen's yeshiva students ''give in to the simplicity of rules rather than the negotiated truce that Deborah seemed to have achieved.'' Even an elderly lady attracts his withering eye: ''Like many Orthodox women of a certain age, she had the look of an aging drag queen.''

Authors who have renounced Orthodox Judaism -- or those who were never really exposed to it to begin with -- have often portrayed deeply observant Jews in an unflattering or ridiculous light. Admittedly, some of this has produced first-rate literature or, at the least, great entertainment, but it has left many people thinking traditional Jews actually live like Tevye in the musical ''Fiddler on the Roof'' or, at the opposite extreme, like the violent, vicious rabbi in Henry Roth's novel ''Call It Sleep.'' Not long ago, I did too.

At 21, I was on the outside looking in, on my first trip to Israel with a friend who was, like me, a Reform Jew. One day, we wandered into a religious neighborhood in Jerusalem, and suddenly there were black hats and side curls everywhere. My friend pointed out a group of men wearing odd fur hats. ''Those,'' he explained, ''are the really mean ones.'' I never questioned our snap judgment of these people until, a few years later, I returned to study at an all-girls seminary and was surprised to discover that my teachers, whom I adored, were men and women from this same community.

The women were a particular revelation. Instead of the oppressed drudges I'd expected, they turned out to be strong and energetic, raising large families and passing on beloved Jewish traditions, quite often in addition to holding down outside jobs. Not all of them had been born into this world: some were newly religious women, former Broadway dancers or scholars with advanced degrees who had now dedicated themselves to performing good deeds. After spending more time in homes like theirs, in Israel and later in America, I came to have a very different view of the haredi, known to outsiders as the ultra-Orthodox.

Some of my Jewish friends have intermarried with people of other faiths; others have gone back to their traditional roots. Because I did the latter, I'm fascinated by the ways different Jewish communities understand and misunderstand one another. As a writer, I'm especially fascinated by how this happens in print. And it seems I'm not the only one. Although some Jewish outsiders, like Allegra Goodman, have written sympathetically of the haredi, other writers have purported to explain the ultra-Orthodox from an insider's perspective. But are these authors really insiders? As I changed from outsider to insider, my perspective changed too.

Consider, for example, Nathan Englander, a talented writer whose collection of stories, ''For the Relief of Unbearable Urges,'' brimmed with revelations of hypocrisy and self-inflicted misery: a fistfight that breaks out in synagogue over who will read from the Torah; a sect whose members fast three days instead of one and drink a dozen glasses of wine at the Passover seders instead of four; a man whose rabbi sends him to a prostitute when his wife won't sleep with him. Of course, the Orthodox don't actually brawl over who reads the Torah, no rabbi is allowed to write a dispensation for a man to see a prostitute, and even extremely pious Jews can't invent their own traditions for fast days or seders. Englander's sketches were fictional, but did most people realize this?

ESSAY; The Observant Reader

By WENDY SHALIT

Published: January 30, 2005

Apparently not. The world at large took him to be a ''former yeshiva boy'' who had renounced his old life. Englander didn't help matters by referring to the ''anti-intellectual'' and ''fire-and-brimstone'' aspects of his ''shtetl mentality substandard education'' -- a strange way of describing the Long Island community where he grew up, which prides itself on its tolerance and dedication to learning, both secular and religious. Englander is about as much a product of the shtetl as John Kerry. He actually attended the coeducational Hebrew Academy of Nassau County and then the State University of New York, Binghamton. It was one of his supposedly substandard teachers who encouraged him to write in the first place.

Englander is one of a number of outsider insiders. In 1978, Tova Reich's novel ''Mara'' depicted an Orthodox rabbi who doubles as a shady nursing-home owner, married to an overweight dietitian so obsessed with food that she gorges herself with five-course meals, even on the fast day of Yom Kippur. The Hasidic hero of her 1988 novel, ''Master of the Return'' (praised by Publishers Weekly for its ''devastating accuracy'') abandons his semi-paralyzed pregnant wife in her wheelchair in order to spit on immodestly clad female strangers; at home, he helps his 2-year-old son get ''high on the One Above'' by giving him marijuana. Reich's 1995 novel, ''The Jewish War,'' told of a band of zealots whose leader takes three wives and encourages his followers to kill themselves. Reich herself prefers not to comment on the level of observance she keeps today, while Englander for his part publicly boasts about eating pork.

Ostensibly about ultra-Orthodox Jews, this kind of ''insider'' fiction actually reveals the authors' estrangement from the traditional Orthodox community, and sometimes from Judaism itself. Unlike Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, assimilated Jews who have written profoundly about the alienation that accompanies that way of life, the outsider insiders write about a community they may never have been part of.

One of the most popular of these is Tova Mirvis. In her first novel, ''The Ladies Auxiliary,'' the Orthodox women of Memphis appear in an unsettlingly harsh light. One of Mirvis's favorite themes is the oddball ba'al teshuvah (literally, ''master of repentance''), a deeply observant Jew who did not grow up as one. Such a type can be seen in ''The Ladies Auxiliary'': Jocelyn, who after years of keeping kosher still regularly indulges in the shrimp salad she hides in her freezer.

In Mirvis's more recent novel, ''The Outside World,'' we meet Shayna, a mother of five girls living in an ultra-Orthodox Brooklyn community. Shayna supposedly chose a more spiritual life as a young adult, yet now she spends most of her time reading bridal magazines. Another character, Bryan, is a 19-year-old who returns home from Israel as a deeply religious radical, renamed Baruch. Yet at his engagement party, he's suddenly starring in a Harlequin romance: out on the porch, Baruch embraces his fiancée and she leans ''in close, their bodies gently pressing against each other.'' It's bad enough that a yeshiva student would embrace a woman not related or married to him, but to do so in public is even worse. Yet Baruch's younger sister isn't surprised: ''They who pretended to be so holy in public were just like everyone else in private. It confirmed what she had suspected: that it was all pretense.''

It certainly seems that way. Shayna's supposedly observant husband, Herschel, ignores his job as a kosher supervisor for the Orthodox Coalition while collecting a salary, without experiencing a moment's guilt. Meanwhile, Shayna has a television in her bedroom, ''its presence an unacceptable connection to the outside world. It had long ago been smuggled into the house in an air-conditioner box to hide it from the neighbors, all of whom had done the same thing.'' All of whom?

There will always be people who fail to live up to their ideals, and it would be pointless to pretend the strictly observant don't have failings. But before there can be hypocrisy, there must be real idealism; in fiction that lacks idealistic characters, even the hypocrite's place can't be properly understood. Like other outsider insiders, Mirvis homes in on hypocrisy, but in the process she undermines the logic of her plot. The novel's jacket copy announces that ''The Outside World'' is meant to explain ''the retreat into traditionalism that has become a worldwide phenomenon among young people,'' but the uninformed reader might wonder why any young person would want to be part of such a contemptible community.

ESSAY; The Observant Reader

By WENDY SHALIT

Published: January 30, 2005

On her Web site, Mirvis says she ''did very little research'' for her books because ''I grew up with all these rules and customs and rituals.'' People who grow up with some traditional customs may imagine themselves experts, but until they've logged real time among the haredi they may know as little as most secular writers. Come to think of it, they may know less, because a secular writer might do more on-the-spot research.

What is the market for this fiction? Does it simply satisfy our desire, as one of Mirvis's reviewers put it, to indulge in ''eavesdropping on a closed world''? Or is there a deeper urge: do some readers want to believe the ultra-Orthodox are crooked and hypocritical, and thus lacking any competing claim to the truth? Perhaps, on the other hand, readers are genuinely interested in traditional Judaism but don't know where to look for more nuanced portraits of this world.

Thankfully for this last group, another sort of fiction has recently appeared, written by some of the newly religious Jews that Mirvis, Englander and others describe but don't quite understand. In real life, thousands of people each year enter the religious fold, and the ones who are writers are bringing with them the literary training of the more secular life they left behind. This makes them ideally suited to act as interpreters between the two worlds.

Consider, for example, Risa Miller, whose ''Welcome to Heavenly Heights'' is a sharply focused fictional portrait of a group of religious American Jews in a settlement on Israel's West Bank. Miller doesn't idealize her characters: they have the same worries and petty jealousies as the rest of us. But she also presents them as people who aspire to transcend their flaws. A ba'al teshuvah since her college days at Goucher, Miller may well have been the first woman to accept the PEN Discovery Award in a sheitel, the wig traditionally worn by observant married women.

Ruchama King is another talented insiders' insider. King is also haredi, though she grew up less observant, and her novel, ''Seven Blessings,'' while ostensibly about matchmaking, is really about the revolution in women's learning among ultra-Orthodox Jews. Like Miller, King doesn't shy away from the problems that affect her world, but she also captures the subtlety and magic of its traditions. In particular, she convincingly describes the sublimated excitement that characterizes ultra-Orthodox dating as tiny gestures take on heightened meaning.

The promising young poet Eve Grubin, who was raised on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and went to Smith College, has recently committed herself to Orthodox Judaism. Her first collection, ''What Happened,'' which explores her faith, will appear this fall.

For now, harshly satirical views of the haredi may still be too common, and novels and stories by sympathetic outsiders like Allegra Goodman too rare. But the emergence of these newly religious novelists is a refreshing development. In their work, age-old customs are being presented in a way that reminds us of the deep satisfactions they can provide, even, or especially, in the face of the uncertainties of modern life. Who knows, they may even succeed in converting some of those outsider insiders.

By WENDY SHALIT

Published: January 30, 2005

JONATHAN ROSEN'S novel ''Joy Comes in the Morning'' features a beatific Upper East Side Reform rabbi named Deborah whose days are spent reassuring insecure converts, studying the Talmud and cuddling deformed newborns whose parents have rejected them. This paragon is, we are told, like a ''plant . . . nourishing herself directly from the source.'' But if Deborah is a plant, she's certainly not a clinging vine. When she propositions a man named Lev, it's with a sexy whisper: ''I'm a rabbi, not a nun.''

In contrast, Deborah's Orthodox ex, Reuben, is a Venus' flytrap. Although he wasn't supposed to touch her, he had no qualms about sleeping with Deborah, a slip she's sure was ''only one of the 613 commandments he had violated, but perhaps the one he most easily discounted.'' Curiously, Reuben showed ''more anxiety about the state of her kitchen'' than he did about spending the night -- next morning, he went through the dishes to make sure she had separate sets for milk and meat.

You might think Reuben is just a guy with a problem, but the problem may also be the author's. In the course of the novel, Rosen dismisses modern Orthodox men as ''macho sissies'' and depicts ''pencil-necked'' Orthodox boys ''poring over giant books instead of looking out the window at the natural world.'' Rosen's yeshiva students ''give in to the simplicity of rules rather than the negotiated truce that Deborah seemed to have achieved.'' Even an elderly lady attracts his withering eye: ''Like many Orthodox women of a certain age, she had the look of an aging drag queen.''

Authors who have renounced Orthodox Judaism -- or those who were never really exposed to it to begin with -- have often portrayed deeply observant Jews in an unflattering or ridiculous light. Admittedly, some of this has produced first-rate literature or, at the least, great entertainment, but it has left many people thinking traditional Jews actually live like Tevye in the musical ''Fiddler on the Roof'' or, at the opposite extreme, like the violent, vicious rabbi in Henry Roth's novel ''Call It Sleep.'' Not long ago, I did too.

At 21, I was on the outside looking in, on my first trip to Israel with a friend who was, like me, a Reform Jew. One day, we wandered into a religious neighborhood in Jerusalem, and suddenly there were black hats and side curls everywhere. My friend pointed out a group of men wearing odd fur hats. ''Those,'' he explained, ''are the really mean ones.'' I never questioned our snap judgment of these people until, a few years later, I returned to study at an all-girls seminary and was surprised to discover that my teachers, whom I adored, were men and women from this same community.

The women were a particular revelation. Instead of the oppressed drudges I'd expected, they turned out to be strong and energetic, raising large families and passing on beloved Jewish traditions, quite often in addition to holding down outside jobs. Not all of them had been born into this world: some were newly religious women, former Broadway dancers or scholars with advanced degrees who had now dedicated themselves to performing good deeds. After spending more time in homes like theirs, in Israel and later in America, I came to have a very different view of the haredi, known to outsiders as the ultra-Orthodox.

Some of my Jewish friends have intermarried with people of other faiths; others have gone back to their traditional roots. Because I did the latter, I'm fascinated by the ways different Jewish communities understand and misunderstand one another. As a writer, I'm especially fascinated by how this happens in print. And it seems I'm not the only one. Although some Jewish outsiders, like Allegra Goodman, have written sympathetically of the haredi, other writers have purported to explain the ultra-Orthodox from an insider's perspective. But are these authors really insiders? As I changed from outsider to insider, my perspective changed too.

Consider, for example, Nathan Englander, a talented writer whose collection of stories, ''For the Relief of Unbearable Urges,'' brimmed with revelations of hypocrisy and self-inflicted misery: a fistfight that breaks out in synagogue over who will read from the Torah; a sect whose members fast three days instead of one and drink a dozen glasses of wine at the Passover seders instead of four; a man whose rabbi sends him to a prostitute when his wife won't sleep with him. Of course, the Orthodox don't actually brawl over who reads the Torah, no rabbi is allowed to write a dispensation for a man to see a prostitute, and even extremely pious Jews can't invent their own traditions for fast days or seders. Englander's sketches were fictional, but did most people realize this?

ESSAY; The Observant Reader

By WENDY SHALIT

Published: January 30, 2005

Apparently not. The world at large took him to be a ''former yeshiva boy'' who had renounced his old life. Englander didn't help matters by referring to the ''anti-intellectual'' and ''fire-and-brimstone'' aspects of his ''shtetl mentality substandard education'' -- a strange way of describing the Long Island community where he grew up, which prides itself on its tolerance and dedication to learning, both secular and religious. Englander is about as much a product of the shtetl as John Kerry. He actually attended the coeducational Hebrew Academy of Nassau County and then the State University of New York, Binghamton. It was one of his supposedly substandard teachers who encouraged him to write in the first place.

Englander is one of a number of outsider insiders. In 1978, Tova Reich's novel ''Mara'' depicted an Orthodox rabbi who doubles as a shady nursing-home owner, married to an overweight dietitian so obsessed with food that she gorges herself with five-course meals, even on the fast day of Yom Kippur. The Hasidic hero of her 1988 novel, ''Master of the Return'' (praised by Publishers Weekly for its ''devastating accuracy'') abandons his semi-paralyzed pregnant wife in her wheelchair in order to spit on immodestly clad female strangers; at home, he helps his 2-year-old son get ''high on the One Above'' by giving him marijuana. Reich's 1995 novel, ''The Jewish War,'' told of a band of zealots whose leader takes three wives and encourages his followers to kill themselves. Reich herself prefers not to comment on the level of observance she keeps today, while Englander for his part publicly boasts about eating pork.

Ostensibly about ultra-Orthodox Jews, this kind of ''insider'' fiction actually reveals the authors' estrangement from the traditional Orthodox community, and sometimes from Judaism itself. Unlike Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, assimilated Jews who have written profoundly about the alienation that accompanies that way of life, the outsider insiders write about a community they may never have been part of.